As inventions go, the camera in all its forms and derivations is an amazing thing. From its inception it was a recorder of information, viewed in much the same way as a surgeon would view the tools of his trade. Naturally though, human nature being what it is, we quickly turned its use into an art form and the making of art. This can be seen as early as the 1840’s & 50’s when early pioneers such as Julien Vallou de Villeneuve and Felix Moulin were producing female nude images. These it is said were used by painters of the time such as Eugene Delacroix instead of having to pay live models. Oddly though it has taken until this century for the establishment to accept photographs as a genuine form of art!

That said, it is something of an enigma that it is the ‘recording of fact’ type images that have and still do create so much conjecture and discourse.

The irony of the camera is that its Achilles heal is us, or to be more precise, the person operating the camera. What we choose to photograph is, often unbeknownst to us, subject to many influences and factors. For instance; Is the Photographer being paid by somebody? Does the individual have their own agenda/reasons for shooting what the do? Do they favour one subject over another? Are there external pressures (e.g. War-zones & being under fire)? All of these things and more can influence what is actually photographed, and equally as important, what isn’t photographed! What is just beyond the border of the image, and why wasn’t it included? Not including something within the frame of the image can significantly alter the context of what is in the frame! The narrative is always partial, and this forms a large part of the conjecture around photography. At best (and even this is a dangerous tightrope to walk) you can only comment on what is visible within the frame of the image. This cannot always be taken as fact! Take the image below:

Fallen North Vietnamese Soldier ( V&A Museum no. PH. 1281-1980 Copyright Don McCullin).

At first glance this looks to be an ‘as it was’ photograph by Don McCullin. He has since said that although the dead soldier had had his possessions pillaged, McCullin himself arranged the personal effects in the foreground so as to create additional impact from the shot. This is achieved by humanising the corpse. Oddly, it is not the corpse that attracts the attention, as the body has no life, there is then no emotion or suffering that we can home in on. Therefore, by putting personal effects up for display, that is where the viewer can start to add their own depth and patina to the image, subconsciously creating a history, story or plot to the image.

Given this, and coupled with the meteoric rise of citizen journalism, that is to say the use of phone camera’s by members of the public, the burning question is; What and who can we believe?

EXERCISE

Just before starting this exercise, the death of Robert Mugabe was announced! So what better place to start this exercise? On the BBC news on 6th September I watched the interview with Peter Tatchell, in which he gives a balanced (In spite of his on-going suffering brought about indirectly by Mugabe) assessment of Mugabe’s political career. On two ocassions Peter Tatchell tried to make a citizens arrest of Mr Mugabe (once in London in 1999, and again in Brussels in 2001). On the second occasion Mr. Tatchell was attacked and left semi conscious (After being hit twice on this video link, he was subsequently attacked again ‘off camera’ where he was punched at least four time, leaving him semi conscious in the gutter), ultimately suffering brain & eye damage, leaving him with balance and attention deficit issues to this day.

The video of the attack on Tatchell could well have been a ‘paparazzi’ recording, but because of the circumstances (jostling) it could just as easily been a bystander. This leads us to the question; Is there any correlation between image quality and authenticity/perceived truth? It is commonly perceived that poor quality images are a more easily accepted as ‘the truth’ than better quality ‘professional photographs’. I think the main reasons for this are twofold; a) Historically ‘Professional media photographers’ have been proven to have fabricated supportive evidence and staged photographs of events (Paparazzi/tabloid journalism), and b) Innocent bystanders and witnesses have reactively captured events that have unfolded in front of them using lesser quality mediums (cellular phones) and have therefore had no ulterior motives for ‘selective’ filming/photographing.

Going back to the Mugabe example, it can be argued that this does not directly implicate Mugabe, as it does not show him issuing an order to subjugate Tatchell. It could just be individuals acting on their own (Im)moral compass. This goes right to the core of the issue regarding power and its abuse. Power can almost singularly be defined as an individual being able to coerce another (for numerous reasons (fear, bribery,threat of physical violence to self or relative or even by exercising charisma!)). However, our judgement of Mugabe is one of recorded systematic and cumulative abuse of power. I think Tatchell knew exactly what he was doing and the risk he was taking and exactly what he could expect. This is why he chose the time that he did, i.e. in full view of the world’s media.

As to the question; Can pictures ever be objective? We first have to realise that before the picture, we have the picture taker. So it is more accurate to ask; Can a photographer ever be wholly objective? The answer to this is yes, in their own mind anyway. However, because of the very nature of the format, there is always pictoral information that is not recorded (beyond the confines of the frame). This does not even take into consideration the sounds and smells and other sensory stimuli that contribute to the recorded situation. For even the most neutral of photographers in any given circumstance, It is impossible to record all attributable information within the frame of a camera.

In the video above, we have to use this information in conjunction with all of the historically collated information we have on Mugabe to build up a more ‘honest’ picture of the man and his actions.

In a scene caught on cellphone video, a police officer in Ivory Coast killed an unarmed theft suspect.

The disturbing image above is taken from an article in The New York Times entitled Inspired by the U.S., West Africans wield smartphones to fight police abuse1. By Dionne Searcey and Jaime Yaya Barry. Published Sept. 16, 2016. The event took place in Ivory Coast. The officer fired several shots close to the man’s head, making him squirm. He then took aim and shot him in the head, killing him outright. In the background, shouts of encouragement could be heard. The man was a suspected thief! Many people are now filming and photographing police corruption across the African states. It is catching on, inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement in the USA, so much so that one country, Nigeria has a program entitled ‘Eye Reports’ which consists of similar videos and stills shot by the general public. It is starting to have an effect on the number of incidences of police brutality, corruption and bribery. As for this image as a stand alone picture, is it objective enough to stand up in a court of law? The poor quality prevents us being able to see the features of either the victim or the officer. This alone negates any efficacy it may have had. Without prior knowledge, there are any number of scenarios we could read into this image. We don’t know that he was unarmed, or even working alone, we could very easily make up a scenario whereby the officer is a public hero, taking out an armed assailant who had been holding a small child hostage. The officer may even have just come across the man laying (in this state) in the street with a gun by his side, the officer just exercising extreme caution!

This photograph was taken by Bill Carter, and appeared in an article in The Guardian newspaper on 22 July 2009 written by Michael White. The photograph shows the distinguished American scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. (Harvard educated and owner of 50 honorary degrees) being arrested by a police officer. Mr. Gates, having returned from a trip abroad found that he had locked himself out of his house. With the help of the taxi driver he broke into his own home. A neighbour saw two men breaking in and called the police. The police turned up, entered the house and asked Mr Gates to come outside. Mr. Gates refused, and was subsequently arrested, taken to the station and had his mug shot taken. The whole issue was, in Mr. Gate’s eyes, about racial discrimination. The arresting Officer is Caucasian, whereas Mr. Gates is black. Mr. Gates took umbrage at what he saw as a white officer making an assumption that because he was black, he was therefore obviously committing a/the crime. The police report has a slightly different slant to it. It says that Mr. Gates, when confronted by the attending Sergeant became irate and confrontational, and was subsequently arrested for disorderly conduct.

What can we say for sure from this image alone? Actually very little, we don’t know if the man in the cuffs has been found in this state of incarceration or whether it was any one of the three uniformed individuals that have put the cuffs on him. We don’t know whether the man has even been arrested. The taker of the photograph has, we assume, watched the whole issue unfold, hearing some or all of the dialogue and taken what to them is a key point photograph. Of course, to the photographer this corroborates what they have seen and is supportive evidence, but to the rest of us it shows very little that we can say for definite.

These images offer up one side of a very polarised view. To even it up, we can look at the work produced by the likes of Dorothea Lange & Walker Evans. In particular the work that they produced for the FSA (Farm Security Administration). They’re work was governed to some extent by the guidelines set out by Rexford Tugwell & Roy Stryker, who set up the FSA. Their brief was to bring to the attention of the public, the plight of the farmers who were effected by the Great Depression of the 1930’s in America. The images that they produced are among the most easily recognised and iconic even today, 70-80 years on. There is a fundamental difference between these and the ones shown above though. The ones above are closely connected with crime/violent death, and therefore we can’t help but see them in an evidential way. At which point we can go no further, as they offer only circumstantial evidence at very best. Lange & Evan’s work, although trying to put across fact to the masses, are only showing representations of accepted fact (The Great Depression caused suffering to many).

Somewhere in between these, sit the work of the likes of McCullin, Capa & Jones Griffiths. In some of their images we are seeing (war) crimes recorded (allegedly!) and in others they are just trying to record the events and conditions of war. Such are the complexities of war and the strong emotions it invokes, all image must surely be viewed subjectively. Can a person be brought to justice for war crimes solely based on photographic evidence?

Documentary and social reform

Although Lange and Evans played a massive part in social reform through the use of the camera, they were by no means the first. About thirty years prior, Jacob Riis was making his mark on history and social reform with his book The making of an American2. In it he bemoans the conditions in which the occupants of the New York tenaments have to live. Going on to say how his writings had failed to draw noticeable attention to their plight, but that he was overjoyed (for obvious reasons) to have found out that a way to shoot photographs in low light had been discovered! At the time, Riis was one of only a few (including Lewis Hines) who were recording the appalling living conditions of the poorest people in a sympathetic manor.

Martha Rosler, in her essay In, around and afterthoughts (On documentary photography)3 argues that Riis’ and his ilk did not realise/understand that society needs tiers and social groupings. Rosler suggests that they should have been championing ‘self help’ rather than charity from the wealthier classes. In summary she says that “This notion of charity is an argument for the preservation of classes it encourages the giving of a little in order to pacify potentially dangerous lower classes”. Furthermore Abigail Solomon-Godeau4 implies that this ‘misdirected’ use of photography within the social arena is ingrained and given the power that the photograph can generate, we still chose to use it to try to reform rather than promote radical or revolutionary change. In doing so we “allow them to be institutionalised by the government so limiting their effect”.

The direct and unflinching approach adopted by W Eugene Smith and his wife Aileen Mioko Smith when championing the people of Minamata, does prove that when employed, “radical” photography can have a profound and lasting effect. Minamata lies on the Bay of Minamata, into which the chemical company Chisso (now known as JNC) disposed of mercury contaminated water for thirty four years. The contaminate was eaten by the fish which were in turn eaten by the people of Minamata. The first signs of defect among the residents was documented in 1956. It wasn’t until 2012 that the area was declared safe, after much dredging and land reclamation. The Smith’s spent three years (they only intended to stay for three months) recording the effects on the people of Minimata. Eugene himself was attacked by employees of the Chisso company and, such was the severity of the attack he was nearly blinded in one eye. Both the government and Chisso alike, stoically ignored the call to stop the dumping, even in the face of mounting, irrefutable evidence. It is largely thanks to the Eugene’s photographic work and Aileen’s written word5 that the dumping finally stopped in 1968, twelve years after the signs started to show.

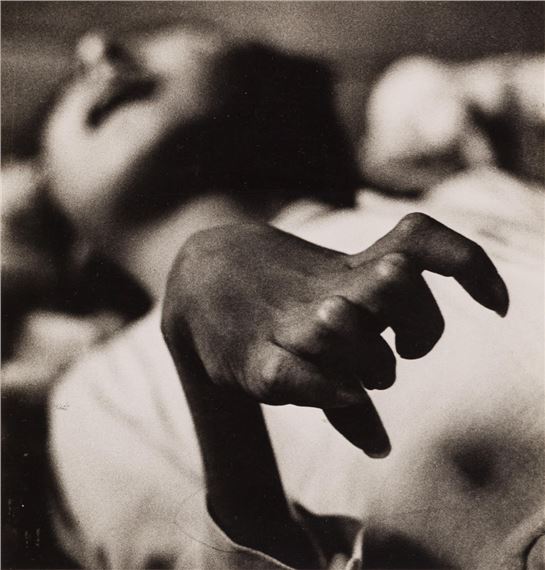

Minamata. Iwazo FUNABA’s crippled hand, a victim of the disease. 1971.

W. Eugene Smith © 1965, 2017 Aileen M. Smith / Magnum Photos.

- https://kennedylive.wordpress.com

- Riis, Jacob, (1901). The Making of an American. New York: MacMillan.

3. La Grange, A,(2008). Basic Critical Theory for Photographers. Oxford: Focal Press.

4. Rosler, M, (1981). In, Around and Afterthoughts (on documentary photography). Halifax: Press of the Nova. Scotia College of Art and Design.

5. Smith, W E, (1975). Minimata. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.